This blog is written by Anyone’s Child campaigner, Brian.

This blog is written by Anyone’s Child campaigner, Brian.

People often say that you can never be prepared for the death of your child. I cannot imagine anything more shocking and distressing, but there are ways in which I had been preparing for it from the moment he was born. I wasn’t ready for it. But I was always aware of the fragility of his life, and did everything I could to prevent harm coming to him. I make no claims for being in any way special for feeling that, for I am sure it is something that every parent feels.

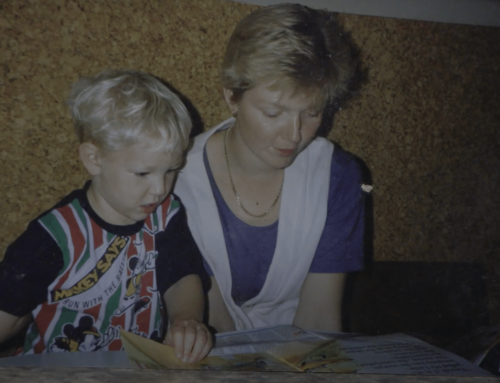

When my son was born, my life changed in ways I could never have anticipated. That’s hardly unusual either. His birth taught me, amongst many other things, new meanings of love. It wasn’t that I hadn’t experienced love before, but the birth of a child encourages a new kind of selflessness that I’d not known before. Putting him first didn’t seem like a sacrifice. The arrival of a child puts a great many things into a very different perspective. From the moment he was born, I did everything I could to protect him. But that need to protect implies an innate fear driven by a recognition of his vulnerability.

I am not a practising Christian, but for most of my adult life I have recognised the insight and the humanity in Christ’s teachings. Before my son was born I had liked to think of myself as a pacifist – although my easy liberal principles had never really been put to the test. His birth challenged that – in the most unexpected way. Christian teaching urges us to ‘turn the other cheek’ if we are slapped or attacked. Whilst the principle of discouraging vengeance is laudable, for me it begged the question, whose cheek do I turn if my child is threatened? Do I turn away? I dreaded my son getting into trouble – whether with his peers or with the police – as most parents do. I knew I would do anything to protect him, but if he was harmed what would I do? Would I seek revenge?

Personally, I don’t believe that the desire for revenge is a specific human trait – or, put in another way, that as a species the desire for vengeance is in some way ‘hard-wired’ into us – but rather that is a cultural norm. Hamlet is one of numerous plays from the late C16th and early C17th , a Golden Age of English theatre, which explore the obsession with revenge. The best of these, such as Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, The Revenger’s Tragedy, The Spanish Tragedy are set in a culture where revenge may be the norm, but the wisdom and morality of taking vengeance is profoundly questioned. Many lesser plays of the period simply celebrate, rather than interrogate the ‘innate’ desire for revenge. And now, 400 years later, we too are immersed in a culture of police procedurals and revenge thrillers, dramatic fictions which constantly reinforce the idea that it is normal to seek revenge and retribution. Indeed, it is hard not to encounter dramatic fictions which create heroes of people who are determined to track down killers, however complex and obscure the causes of death might be. Those same stories rely on there being villains to go after.

Combine that cultural immersion with this sense that most people would do anything to protect their children, and it is not surprising that people want to see drug dealers locked away. Those feelings may be partly driven by a generalised sense of seeking revenge against those characterised as callous, greedy and brutal. But it is also driven by fear for the safety of their own children. ‘Those people’, the others, the users the suppliers, the dealers, they are the villains. Put them behind bars and the problem goes away. If only it were so simple.

My beloved son died in April 2020, three days after his 37th birthday. Because of Covid 19 regulations and restrictions, the inquest into his death did not take place until July of this year. The coroner’s findings were that his death was a result of the combined effects of heroin and alcohol, although the quantities of each was insufficient to have been fatally toxic on their own. The coroner was satisfied that his death was accidental, and there was no intent – on his part, nor on anyone else’s – to end his life. The inquest was as humanely handled as it is possible for such things to be, but it begged so many questions. which I suspect will never be answered.

When I asked the representative of the police who attended the coroner’s inquest if they had been able to find out how he got hold of the drugs or who might have supplied them to him, they said they had no idea. They removed his phone, laptop and tablet when they attended his death, then contacted me within a week to say that they no longer had any interest in them. When I collected them from the police station and tried to get more information, their lack of interest was very evident; the unstated implication was clearly that accidental deaths such as my son’s were not only common, but that it was pointless trying to pursue small time dealers and users.

Some people might have been tempted to try to track down the person who supplied him with the heroin that contributed to his death. But even if I had been able to find the person and had enough of my wits about me to have a genuine dialogue with them it would not have changed anything, and would certainly not have eased the pain of my loss. Some people might feel an appropriate response would be seek a prison sentence for them. And I’m sure I would have felt that desire for vengeance much more strongly if my son had still been a child; but if the long term aim is to prevent that person from supplying others, a prison sentence – at least given the current prison regime – would have been horribly counter-productive.

Over the past eighteen months, I have sometimes wondered whether there was something ‘wrong’ with me in not feeling the desire for vengeance. It has not been an ethical or moral decision, but rather a pragmatic one based on my own personal experiences of how the criminalisation of drug use and drug dealing affects people. I’ve worked on several theatrical projects in prisons, and most of the inmates I worked with were doing time for drug and drug-related offences. When I began the first project I remember vividly someone saying to me that prisoners fall into one of three categories: the sad, the mad and the bad. Although the incidence of serious mental health issues is rising fast in the prison population, it was quickly evident to me that the majority of those I was working with were profoundly sad. Very few were going to leave prison with any sense of real hope that they could improve desperate social situations; and prison had destroyed self-esteem and shut down their options, rather than creating opportunities for changing their lives for the better.

My son never got into trouble with the police over his drug use. But he suffered greatly from the stigma associated with it. It is one of the awful ironies associated with his death that in recent years he had begun to open up about those feelings. He spoke openly about the sense of shame, of being trapped in a vicious downward spiral of drug use to ease emotional pain leading to a sense of isolation, the isolation increasing his sense of inadequacy, and that in turn leading to desperation and a retreat to further drug use. A punitive response to the pain he was already feeling would almost certainly have made it more difficult for him to deal with his own pain.

It is all too easy to demonise the person who supplied him with drugs, but it doesn’t take much imagination to see how likely it is that he or she struggled with similar issues.

I rail against the hypocrisy of politicians, many of whom are far better informed than the right wing press about the realities of the effects of attempting to regulate drug use through criminalising use and supply. But if we are to persuade people to change drug laws and drug policies we have to understand that the impetus to criminalise is driven as much by fear as by any rational understanding of the ways that the drug laws actually work. We have to persuade people that their children are in greater danger from the present system than they would be in a society in which drugs were carefully regulated, and that those in psychological pain were offered social and emotional support, emotional support instead of punishment.

The prohibition of alcohol doesn’t prevent alcohol abuse. It increases levels of violent crime as competing criminal gangs take over the supply chain. Changing the laws so that drugs are regulated rather than criminalised is not a panacea – the regulation of alcohol doesn’t prevent alcohol abuse. But if the regulation and supply of drugs were undertaken by those with an interest in the well-being of users, rather than by criminal gangs whose only interest is financial exploitation, our children would be protected far more effectively than they are now.

Powerful, thoughtful and persuasive, Brian.

A profound piece, telling many truths. I can relate to much of this. Thankyou

“Emotional support instead of punishment” It is such an obvious approach. Brian’s is a moving and persuasive argument.

Agree totally and admire your brave sincerity.

The drug laws desperately need to change for all our sakes.

The laws are outdated and counter productive.

Only a few months ago I listened to the whole 3 hours of the cross party parliamentary debate.

The consensus was strongly in favour of reform. What happened? When will changes be made?

Agree, stigma and the fear that closes minds do so much harm.

Great piece, thank you.