On the other end of the line, Officer Peter Muyshondt closed his eyes and breathed deeply. Not again.

“Thanks for the heads-up,” Muyshondt replied in Dutch, the dominant language in his hometown of Antwerp, Belgium. “I’ll be down to see him.”

He hung up the phone, overcome with anger and disappointment. It was embarrassing enough to drive by Antwerp’s most notorious drug corner each day in his police cruiser, watching his little brother Tom breaking the laws Muyshondt was sworn to uphold. But to visit Tom in jail each time he got arrested, to pretend he didn’t notice the stares and whispers of fellow law enforcement as they gossiped about the officer with a criminal brother… It was more than he could take sometimes.

With a sigh, Muyshondt headed to the jail. After security checks, he sat across from his brother in the visiting booth and picked up the receiver, their only communication through the thick plexiglas wall. He meant to reprimand Tom, but one look at his brother’s cheeky grin and Muyshondt couldn’t stop the smile that spread across his face.

“So, the good guy finally showed up to visit the bad guy!” Tom joked.

Muyshondt laughed, and suddenly, they were kids again, two brothers sowing mischief over the rural county where they grew up in central Belgium, trying to protect each other from the volatility of their home life. As teenagers, they had each found their escape: Peter, to a regimented military high school where discipline and rules helped him cope with a chaotic childhood; Tom, to a life in which drugs helped him do the same.

At that time, “I was really believing that my brother being punished by criminal court would help get him off addiction,” Muyshondt told Filter in an interview in Brussels. Still, he admits that watching his brother go through the cycle of drugs and prison made him question police tactics.

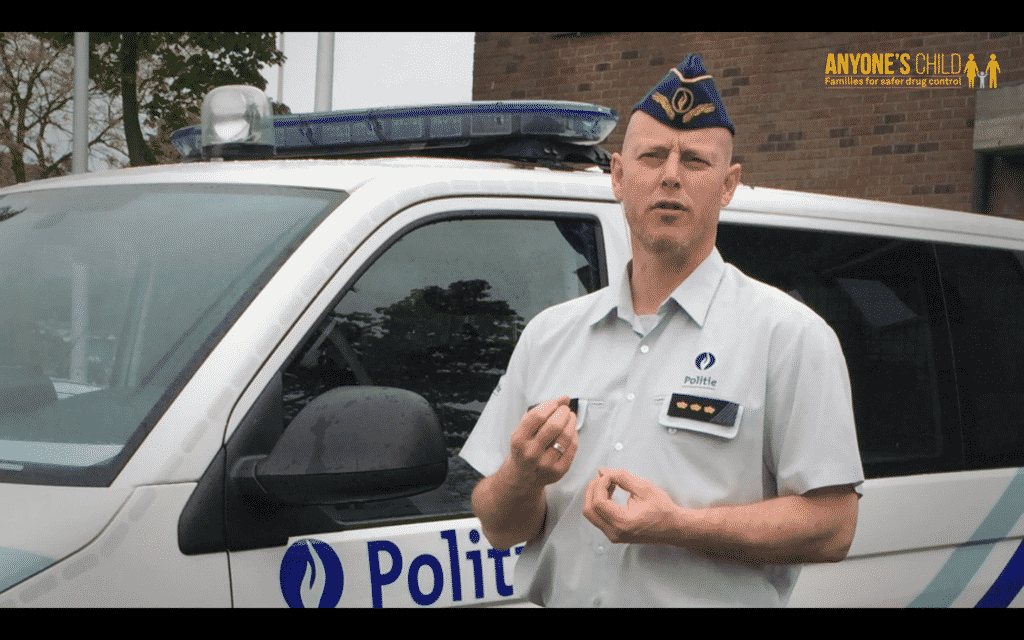

When you have a family member who uses drugs “you are getting information you don’t want that is right in your face “Frustration and anger against everything and nothing.” Despite the risks of incarceration and unregulated street drugs, Muyshondt believed his brother would pull through. So he wasn’t expecting the call in July 2006 informing him that Tom had died of an overdose. A week earlier, Muyshondt had visited Tom at a rehab facility. As usual, the two had laughed and joked—in this case about the birdhouse-making classes that Tom was forced to attend as part of his therapy. Muyshondt described his feelings at learning of his brother’s death as “frustration and anger against everything and nothing.” Tom’s death marked a turning point in Muyshondt’s attitude towards drugs and drug policy. No longer did he think that punishment would stop a person from using. In fact, he didn’t think that drugs themselves were the problem. Instead, he began to speak out publicly against prohibition, which spawns a lucrative illicit market, and locks people like his brother into a perpetual cycle of prison and the streets. “Prohibition isn’t working,” said Muyshondt, who has written two books condemning the ineffectiveness of policing against drugs. He argues that only legalization and regulation of drugs will dry up the illicit market and allow communities to focus on preventing addiction. The notion that working to change police officers’ views is an important strand of the reform movement is highly controversial for many in the harm reduction community. Many people, including those who have had traumatic experiences at the hands of the police or know others who have, view engagement with police as inappropriate, or even as “collaboration.” Recognizing these realities does not contradict the urgency of also seeking deeper, systemic change. When I wrote about police harm reduction work and the surrounding controversies for Filter last year, I received a flood of responses, many of them critical. Some on social media accused me of “shilling” for law enforcement. I’m not. If harm reduction is about meeting people and situations “where they’re at,” and striving to improve things by not making the perfect the enemy of the good, these are difficult conversations that we need to have. Police cause great harm in the course of the drug war, which they help to sustain through their advocacy, and officers’ conversions therefore reduce harms. And for many sections of the population, current or former officers’ advocacy against the drug war is particularly compelling. Recognizing these realities does not contradict the urgency of also seeking deeper, systemic change. Muyshondt’s story may be unique because he had a brother to help open his eyes to the realities of why people use drugs and how prohibition increases overdose deaths. But in other ways, his story is similar to those of others who have become advocates for drug policy reform during or after long careers in law enforcement. Many, if not most, people get into police work because they want to serve communities by fighting crime. But as the years go by, starry-eyed optimism often gives way to doubt as they see the same people arrested again and again, as the drug dealer they took out is quickly replaced by another, as they realize that prison is more a brutal training ground for illicit behavior than a deterrent. Muyshondt believes that the key to changing police hearts and minds about the drug war is for them to receive the message from fellow officers. A few conversations among law enforcement, many of whom are already retired, might not seem like enough of a catalyst for sweeping change. Certainly, it’s not the only way to challenge the drug war. We can and should also reform drug laws, address systemic racism within society and law enforcement, dismantle the systems of perverse financial incentives that keep the drug war entrenched in the criminal justice system, and replicate the work of state and countries that have already decriminalized or legalized some drugs. But with law enforcement actively fighting against these changes, as they often do, it will be hard to see progress. At the very least, we need a critical mass of law enforcement to do what Muyshondt has done—first, stop doing harm. Then make amends. “Police are easy followers,” said Muyshondt with characteristic bluntness. He seems to believe that if the winds of change shift direction on drugs, law enforcement will follow the new trends as devotedly as they now follow current ones. Systemic change, even revolution, starts with individual conversations. At first it might not seem like a few new allies would have much effect on the system as a whole, but those allies are the dry brush waiting for a spark. The job of active and retired law enforcement who know the truth about the War on Drugs is to lay that brush, so when the fire finally catches, there will be no stopping it.A Legitimate and Vital Strand of Reform

Hearts and Minds

Leave A Comment