“The Sheffield: Take Drugs Seriously event provided the platform for discussions on drug policy reform, harm reduction, and the broader socio-economic implications of prohibition. Members of the local community and the city’s stakeholders came together and engaged in a critical dialogue about the failures of punitive drug policies in the UK and explored alternative, pragmatic approaches rooted in public health.”

On the evening of 6th of February 2025, as dusk descended over Sheffield’s distinctive skyline, the Park Community Action Centre, prominently situated high upon Park Hill, served as the venue for the latest Anyone’s Child event:

Sheffield: Take Drugs Seriously.

With a sweeping view of Sheffield city centre, Park Hill holds the title of the largest listed building in Europe, built in 1961 as a bold vision for a new kind of community living. Designed with ‘streets in the sky’—broad walkways outside each home wide enough for a milk float to pass—these spaces became vibrant hubs where families gathered and everyday life flourished.

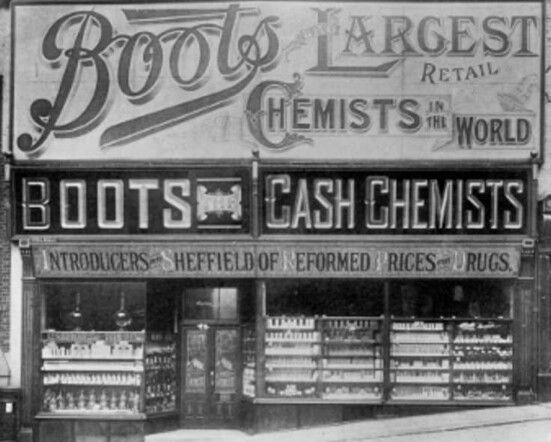

Sheffield, historically known as the “Steel City,” was a major hub for steel production and manufacturing during the Industrial Revolution, fueling economic growth but also contributing to poor working and living conditions. The iconic history of the city differs in many ways from the Sheffield of today. Substances such as opium and cocaine were sold in pharmacies and commonly used for medicinal and recreational purposes with minimal legal restriction. Opium was a staple in many working-class communities, alleviating pain and exhaustion from gruelling labour conditions. However, as societal concerns over drug dependency and morality grew, regulatory measures began to emerge. By the early 20th century, policies such as the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1920 criminalised possession and unlicensed distribution of substances like heroin and cocaine, marking a shift toward prohibition. This evolution—from regulation and accessibility to strict criminalisation—has shaped the drug policies in place today, despite increasing evidence that prohibition exacerbates harm rather than reducing drug use.

This shift in policy is particularly relevant to Sheffield, a city historically defined by its industrious spirit, which now ranks in the top third for drug-related crime in England and Wales, with rates reaching 112% of the national average. Sheffield’s drug market, driven by organised crime and fuelled by prohibition, is not unique; towns and cities across the UK face similar challenges. Yet, Sheffield’s rich industrial past makes the shift in its social and economic landscape particularly poignant. As attendees arrived, whispers soon spread of a police cordon just two streets away, a stark reminder of the societal issues we face today.

Inside the hall, at the very centre, was a striking display of 4,790 handmade forget-me-not flowers. Each flower symbolised a a life lost in 2023 to failed UK drug policies. The names and messages handwritten on the flowers reinforced the devastating reality of the avoidable tragedies. Toward the rear of the hall, a mock-up Overdose Prevention Centre (OPC) demonstrated how dedicated, safer environments for people who use drugs can be inexpensive and used as a pragmatic response to the toxic drug crisis gripping communities.

The event was chaired by Jane Slater, CEO of Transform Drug Policy Foundation and Campaign Manager for Anyone’s Child: Families for Safer Drug Control. Marking the first in a series of events of the 10-year anniversary for the Anyone’s Child campaign, Jane spoke with passion; about how she has witnessed two decades of ineffective drug policies and each year increases in preventable loss. A direct cause of prohibition. Jane’s message was clear: behind every statistic is a human tragedy that could have been prevented.

Adding a deeply personal perspective, Anne-Marie Cockburn, a founding member of the campaign, recounted the loss of her only child, Martha to an unintentional MDMA overdose. “Martha did not intend to die, she just wanted to get high”. Anne-Marie emphasised that if local drug checking and testing services were available and products were legally regulated with ingredients and dosage information, Martha could have made an informed decision that might have saved her life. Anne-Marie concluded her powerful speech with a simple request. “Please share this story with at least 3 people.”

To follow Anne-Marie as speaker is an incredible task, but Chris Bradey served as a perfect segway. He provided an overview of his decade-long work with The Loop, the UK’s pioneering, first and only drug-checking service. From the humble beginnings of a handful of festival welfare volunteers, to the present day, which now sees The Loop – their chemists, harm reduction and research teams – providing regular front-of-house drug checking in Bristol, back of house testing at festivals and nightclubs. The Loop also have a team of trainers who deliver online harm reduction training packages and travel up and down the country educating stakeholders, police, drug services and organisations in the nighttime economy.

Expanding on the broader social implications of punitive drug policy, Becky Rawnsley shed light on how childhood trauma and adverse experiences often push young people toward drug use. Instead of receiving support, many find themselves criminalised, further entrenching their struggles. Her contribution reinforced the argument that punitive drug policies fail to address root causes and instead perpetuate cycles of harm.

Building on this, Danny Ahmed presented compelling evidence from Middlesbrough’s Heroin-Assisted Treatment (HAT) program. This cost effective intervention for individuals who are unresponsive to conventional treatments, HAT has demonstrated clear benefits: improved quality of life, reduced crime rates, and increased engagement with health services. Despite the clear success, this service has been shut down due to a change in Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC) who cut the funding on their first day in post.

Further emphasising the need for a community-driven approach, Vicki Beere, former CEO of Project 6 and now Vice Chair of Transform Drug Policy Foundation, stressed the critical role of co-produced initiatives in harm reduction. and for drug services to advocate for change and put pressure on policymakers. Vicky left the audience with a very clear message that many overdose deaths could be prevented if drugs were legally and responsibly regulated, providing a safe supply for people who are using drugs.

Former undercover officer Neil Woods then delivered a striking critique of law enforcement’s role in exacerbating drug market violence. He explained how aggressive police interventions only serve to empower organised crime, making drug supply even more dangerous. Drug busts, he argued, do not decrease overdose rates; evidence proves they increase them. His message was unequivocal: legal regulation of the drug market is the only viable solution to dismantling organised crime and ending the exploitation of young people involved in county lines operations. The UK’s decades-long policy, he concluded, is a catastrophic failure.

During the question-and-answer session, attendees engaged in discussions with the panel concerning harm reduction in the nighttime economy, the criminal justice system, and the implementation of policy reforms in Sheffield. There was a shared understanding that, while national services must enhance their efforts, it is often community and grassroots organisations that are capable of effectively implementing strategies that mitigate harm in the short term. However, sustained change necessitates national intervention – Drug policy reform is needed to increase efficacy in frontline practice.

Over the past five decades, drug policies in the United Kingdom have failed to safeguard lives.

The collective sense from the community members, bereaved parents, frontline workers, academics, people who use drugs, journalists, researchers, and council members in the room was that change is not only necessary—it is long overdue.

Beyond the tragic loss of life, drug prohibition also leaves communities fractured, families torn apart, and individuals locked in cycles of poverty and incarceration. Criminal records for minor drug offenses can limit access to education, employment, and housing, perpetuating a cycle of marginalisation. The stigma surrounding drug use discourages individuals from seeking help, further exacerbating the crisis. Rather than protecting society, prohibition has created deeper divides, eroding trust between communities and the institutions meant to serve them. Reform will not only save lives—it will restore dignity, opportunity, and social cohesion. After all people have the right to know what they put into their bodies.

As we prepare for our annual lobby of Westminster, taking place on the 24th of June 2025, we’ll be holding a number of online and in person meetings. These meetings connect regional activists and networks across the UK, as we all come together for the 10th year of the campaign. If you would like to join our UK national activist network, learn more about regional networks or how to set one up, please don’t hesitate to get in contact: dave@transformdrugs.org

Leave A Comment