This blog was written by Anyone’s Child coordinator, Mary.

August 31 is International Overdose Awareness Day, a time to remember those who have died by drug overdose and raise awareness about overdose prevention and drug policy.

This year, the IOAD 2023 theme is Recognizing those people who go unseen. It is a call to acknowledge the people in our communities who are affected by overdose: the family and friends grieving the loss of a loved one; workers in healthcare and support services extending strength and compassion; or first responders who assume the role of lifesaver.

Corporación Viviendo is a Colombian NGO with a community harm reduction programme for people who inject drugs in Sucre, a neighbourhood in the city of Cali, where I have been volunteering for over a year as part of my PhD fieldwork.

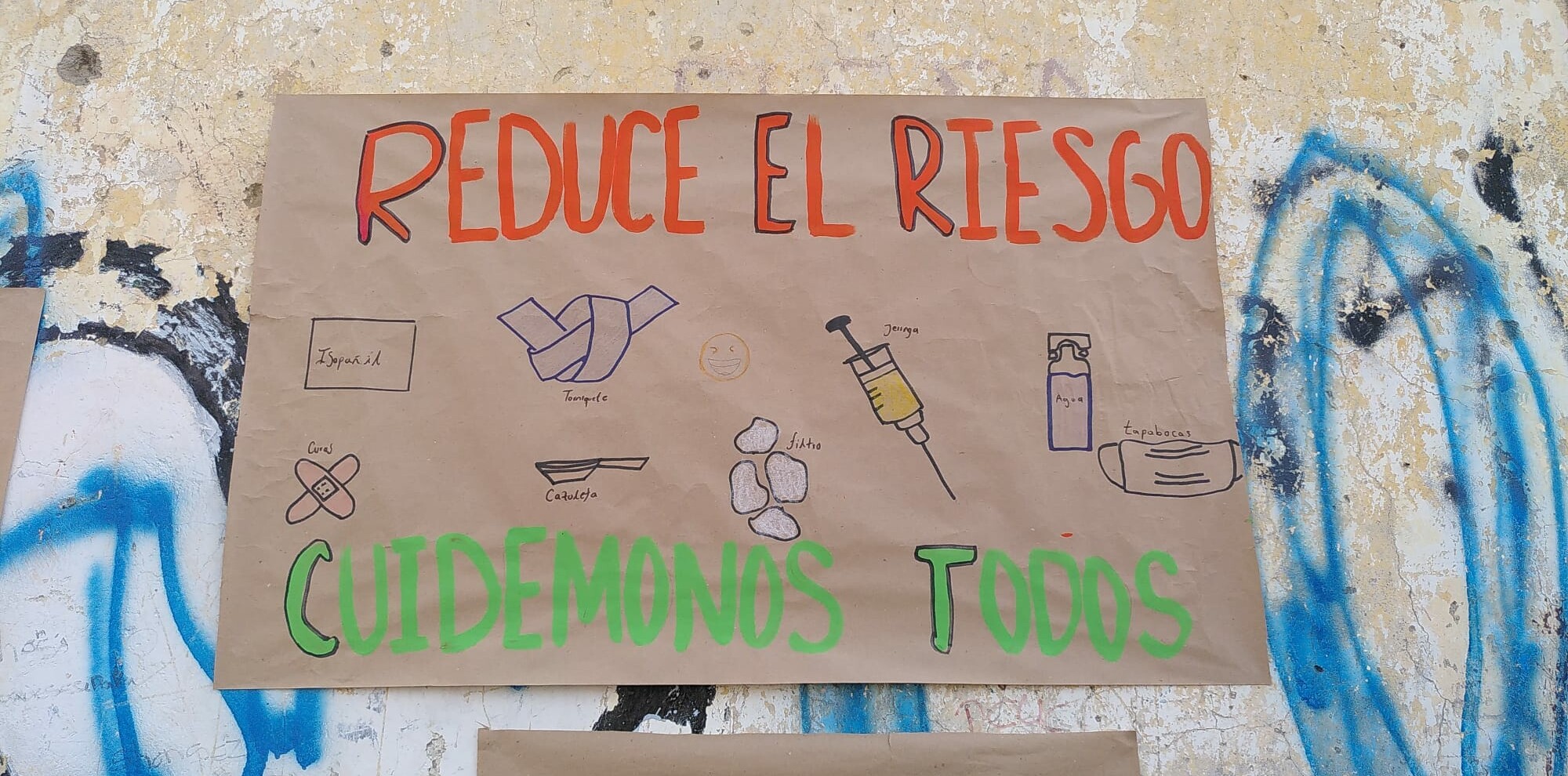

To prevent overdose deaths, reduce drug-related harms and improve the quality of life of the Programme’s users, Viviendo provides hygienic injection material, basic services, medical care, safer injection education and advice, and naloxone training. The community-focus is key here; Viviendo has also generated a network of allies, institutions and community leaders which respond to the needs of the people who use drugs and the neighbourhood’s residents, to improve inclusion and well-being across the whole of Sucre.

I cannot stress enough how challenging a context it is. In many parts of Colombia, the stigma around drug consumption is experienced so viscerally that people who use drugs have become targets of discrimination crimes, as threats and violence are deemed a valid and desirable way to deal with people considered ‘disposable’, ‘flawed’ or ‘dangerous’. This, coupled with inequality, extreme poverty, exclusion, and the lack of mental health support result in many people who use drugs in Colombia being severely marginalised and under-served.

Coming across the work of Corporación Viviendo filled me with hope. It was refreshing and inspiring to find a place where people who use drugs – many of whom have been victims of this stigma and violence – are treated with dignity and compassion, where they feel accepted and not judged, and where abstinence is not imposed as a goal. However, when someone in Sucre dies because of drugs, the whole community is affected as friends and family, first responders and professional workers simultaneously, and this takes a toll

In the last year, 513 people who inject drugs have accessed the services; an average of 120 people attend the point of care daily. Remarkably, regular naloxone training and the strong community response mean that there has been just one recorded death from heroin overdose among the Programme’s users since 2021. This marks a huge achievement and is hopefully testament to a change in attitude towards people who use drugs in Sucre.

However, despite Viviendo’s interventions, the living conditions of the people we support are extremely challenging. Life on the street limits access to health services, hygienic spaces for injection, and access to food in dignified conditions, while exposing individuals to theft and violence. In addition to overdose, people who inject drugs are at increased risk of HIV and hepatitis B and C, often transmitted through shared needles, as well as tuberculosis. Stigma and discrimination further undermine access to the health system and mental health services. For example, people are frequently denied entry to hospitals because of their appearance, or are treated so poorly that they avoid going. Recently, someone recounted how they were turned away by the emergency services after having been stabbed; “you are going to die soon anyway because you consume heroin,” a nurse told him. In this struggle to access the right to health, many die from advanced diseases and lack of care and attention.

A spate of deaths in Sucre in April and May had a massive impact on me. You feel the loss of each person individually, and know that the world is not a better place without them. The overwhelming nature of the grief and the despair at the complete abandonment and neglect of people who use drugs in Cali began to feel too heavy. There was no time to process or heal because then somebody else would die. You can’t stop working and close for a few days because this would have potentially devastating implications on the community as well.

While the risk of ‘vicarious trauma’ and ‘burnout’ for people attending overdoses and working in drug treatment are very real, as frontline worker Zoe Dodd’s points out, this might indicate that workers are mentally ill, or broken on the inside, or don’t have enough resiliency. But in this context we are dealing with so many tragic deaths. Feelings fluctuate between deep sadness, rage, anger and hopelessness. Sometimes there is a degree of solace to be found in the knowledge that people passed away with dignity, that they were being accompanied by staff at Viviendo who were doing everything within their power to help. But for the most part, it is hard to accept deaths that are entirely preventable by better drug policy and government support. It is very distressing to know that whatever it is that you’re doing is not going to be enough.

For members of the team who have worked in Sucre for a long time, these can be people that they have known for years. They are connected in the community. It is a very complicated grief.

On the Support Don’t Punish Global Day of Action we made Ojos de Dios (God’s eyes) to commemorate and honour lives lost to drug deaths in the community. This is a spiritual object made by weaving a design on a wooden cross, to this we attached the names of people in the community who had died. I will never forget seeing someone picking them up one by one, as they brought memories of all his peers who had passed away. The cumulative impact of having known and lost so many people is intense and leaves a huge mark.

Clearly, so much more needs to be done. The World Health Organisation acknowledges that removing punitive laws, policies and practices, reducing stigma and discrimination, community empowerment, and addressing violence are each necessary to prevent more deaths.

Corporación Viviendo works to tackle and address all of these issues. For decades, drug policy in Colombia has prioritised a punitive approach to drugs over policies based in harm reduction and public health. Yet Viviendo’s capacity to prevent and respond to overdoses has saved many lives. In a context where stigmatising and even killing people who use drugs has sometimes been the default, this is a remarkable achievement. There is a lot we can learn worldwide from Viviendo’s community harm reduction model, and working collectively to address overdose and other drug-related harms.

Leave A Comment