This blog was written by Hannah Manwell, Masters student at University of Bristol and Anyone’s Child Intern.

Written by the former drug-dealer Niko Vorobyov, Dopeworld promises to take its readers around the world, exposing the social and economic impact drugs are globally bearing. Opening with the distressing image of ‘blood and brains … on the sidewalk’ in the Philippines’s capital, the dark reality of the War on Drugs is palpable.

Vorobyov candidly shares his personal relationship with the world of drugs throughout the book, sharing his experiences selling drugs at university, being sentenced to two and a half years for possession with intent to supply, and his time in HM Prison Isis. He also stresses his middle-class upbringing, living in Russia, America and Bath (UK), and the academic accomplishments of his parents. This reflects the notion repeatedly reiterated by Vorobyov, drugs can affect everyone regardless of their demographic status. However, this is not without inequities.

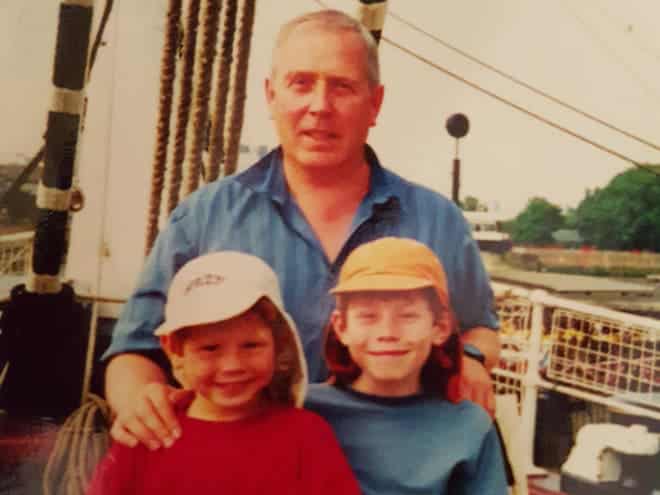

The failure of the War on Drugs is persistently made transparent, for instance in 2018 ‘Mexico’s annual body count for its drug war … reached over 33,000 murders’, recapitulating the commonality of the opening scene set in Manila. When prohibiting laws are made, there are constantly innovative and dangerous strategies generated to evade them; from El Chapo’s tunnels to drug mules, the demand and thus supply around the world is relentless. The human detriment as a consequence of the futility of these laws is manifested in Ray Lakeman’s loss of his two sons, Jacques and Torin.

After obtaining ecstasy from the ‘Dark Web’, both of Ray’s sons lost their lives after taking ‘six times the lethal dose’. Vorobyov openly posits his anxiety ahead of meeting Ray, but it is not the drug-dealer Ray blames; it is the system. Ray asserts that there are laws, but these laws do not work and so change needs to ensue. If Jacques and Torin had known exactly what they had bought and how strong it was, their deaths would have been prevented. Vorobyov elucidates this using alcohol as an analogy: ‘Imagine if every time you took a swig from a bottle, you were taking a gamble in it being anywhere between a normal beer (about 4 per cent) or absinthe (up to 80 per cent). That’s how people die’, underlining the need for regulation.

The history of drugs in our ancestor’s culture and the impact of the War on Drugs since 1971 demonstrates that prohibition has not been successful; drugs are tied up in the social and economic makeup of our present world. Vorobyov gives examples of countries which are paving the way, and while there has been progress in the UK with organisations such as The Loop, it is important the discussion does not become stagnant. Presently, there is still a human cost to the laws that are in place, and a change in these could protect those who have previously been neglected.

I think that Vorobyov effectively fuses autobiography, journalism and history with a humorous style that proves to be a provocative and engaging read. It is highly recommended if you are seeking a varied and assorted insight into the complexities of the past, present and future drug worlds.

Watch Ray’s story here.

Leave A Comment