Today our thoughts go to all of the families who have lost a loved one to a drug overdose.

During 2017 in England & Wales, there were 2503 deaths. That’s 7 a day, 48 a week, 209 a month. There are now more drug-related deaths than there are road traffic deaths, and each one is entirely unnecessary and preventable.

Behind these statistics are the devastating real-life stories of the families that been impacted and are now suffering in growing numbers. Each of these people is someone’s brother, sister, child, or partner. Read their individual stories here.

Families in Kenya, Mexico, the UK, Canada, Belgium and now Australia are standing up for the human rights of people who use drugs and their families, fighting the stigma around drug use and speaking out about the urgent need to reform drug policy.

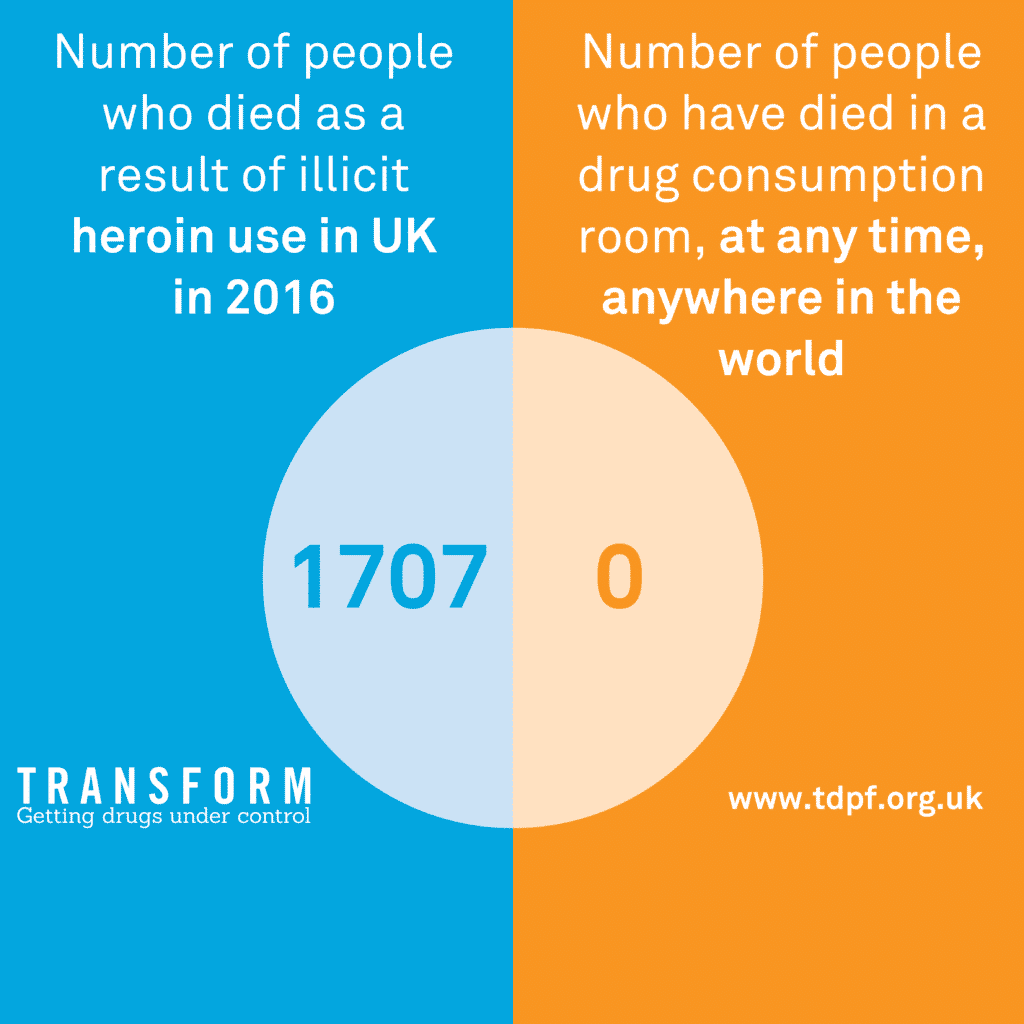

We are calling on governments to address this crisis now – they are responsible for vulnerable people dying. To save lives governments must fully-fund drug treatment, stop criminalising people who use drugs, and allow supervised drug consumption rooms. Ultimately we need to legally control and regulate the drug market to take it out of the hands of criminals to prevent more needless deaths.

Today we are also launching the story of the newest member to our group, Kaye, whose daughter, Catherine, tragically died of a heroin overdose. This story also illustrates the effectiveness of the Anyone’s Child campaign to win over hearts and minds through the emotive power of a mother’s testimony.

I begged Premier Andrews to change his mind, for all the kids like Catherine.

Despite resonant objection to safe injection rooms, Kaye helped to persuade the Premier of the State to trial one, and in doing so, has helped to save the lives of many vulnerable people.

Kaye’s story

My daughter Catherine died in Melbourne, Australia.

She was eighteen and my only child; smart, kind, and feisty. She had the most beautiful hands. Square and broad, with long, slender fingers. Expressive hands people used to say. For years she cracked her knuckles. She said the joints popping felt good but I worried she might get arthritis and bribed her with a hundred dollars to stop. She did, though later confessed she occasionally cracked them when I wasn’t around.

She was eighteen and my only child; smart, kind, and feisty. She had the most beautiful hands. Square and broad, with long, slender fingers. Expressive hands people used to say. For years she cracked her knuckles. She said the joints popping felt good but I worried she might get arthritis and bribed her with a hundred dollars to stop. She did, though later confessed she occasionally cracked them when I wasn’t around.

My daughter was found unconscious on a concrete stairwell.

She was risk taker and known for speaking out against injustice. At eleven, she stopped eating meat permanently when she learned about animal cruelty. After graduating from the Waldorf School, she took a gap year, traveling to Melbourne with a girlfriend. She didn’t tell me she dabbled in heroin. When she overdosed, her body literally forgot to breathe.

Last year, I wrote to Daniel Andrews, the Premier of the State where Catherine died. I knew he was a man of principles. When he was Health Minister, he grappled with his conscience over the Abortion Law Reform Act. As a devout Roman Catholic, it must have taken great courage to go against senior church clergy who advised the Act was contrary to Church teaching. I asked him to show similar courage by trialling a safe injection room, even though he had made an election promise not to do so. I appealed to him as a father. Imagine your worst nightmare, I wrote, losing one of your kids. Wouldn’t you do everything in your power to keep them safe? There are currently more than 100 safe injecting facilities and the overwhelming evidence is that they do not increase drug use but do reduce drug overdoses, the spread of HIV and hepatitis C, and discarded needles in public places. I begged Premier Andrews to change his mind, for all the kids like Catherine who make stupid mistakes. Don’t let them be fatal ones, I concluded. If there had been a safe injecting room, perhaps my girl wouldn’t have gone to a secluded place and died before the paramedics arrived.

Six months later, Premier Andrews did change his mind after meeting with families who have lost loved ones to heroin.“To stubbornly continue with a policy that’s just not working, then that’s the wrong thing to do when there is an alternative,” he said.

Today, I’m working on a documentary called Catherine’s Kindergarten about my personal journey of healing and forgiveness. It also challenges the stereotypes surrounding drug users, cutting through the “us” and “them” mentality as cleanly as a wet knife slices through warm cake, demonstrating we are deeply connected and all in this together. And it presents a call to action to change the draconian drug laws from a criminal justice to a public health model, like in Switzerland. I hope Premier Andrews will see my film one day.

Anyone’s Child is a growing network of families. If you’ve got a story to share please email info@anyoneschild.org

Leave A Comment