This is a blog by Jane Slater, Campaign Manager for Anyone’s Child

I’m headed to Kenya next week for work I told my friends – Really? The response. Does Kenya have a particular drug problem? Why are you headed there? My reply, where doesn’t have a drug problem? Here’s my story of why I went and what I discovered on my Kenyan drug policy reform campaign journey.

We were off to launch Anyone’s Child Kenya – the latest extension to our successful campaign. Anyone’s Child is a growing network of families whose lives have been destroyed by the drug war, who speak out for the need to legalise and regulate drugs.

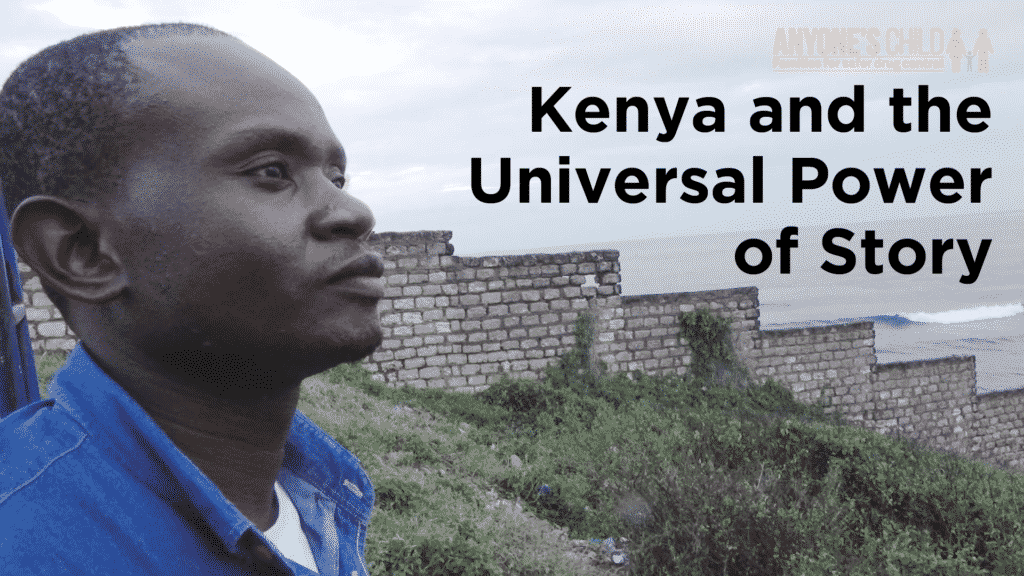

I first met Lugard, the Kenyan founder, a few years ago at our office in Bristol. He visited as an African fellow on a training programme organised by Release. I’d mentioned the Anyone’s Child campaign and how we were trying to tell the real stories of the drug war, and he’d told me the story of his friend who had died from police brutality because of her involvement with drugs. He mentioned how much it had impacted him and driven him in his work (read more here).

We then invited him to attend the 2016 United Nations General Assembly meeting in New York, where we held a rally of families from across the world who wanted to change the debate around drugs. The mood was clearly both rallying and inspiring, and Lugard returned home and felt compelled to set up his own extension of the Anyone’s Child campaign in Kenya – an African first!

On arriving in Mombasa, we started our week with a visit to the Reach Out Centre, the leading harm reduction provider in the city, and where Lugard has worked for over nine years as an outreach worker. It offers a truly pioneering service – clean needles, HIV testing, health advice all in a non-judgemental holistic manner. I understand that some staff have been imprisoned and harassed by the police for delivering this service. Meeting many of the workers involved and seeing the progress they’ve made was both inspiring and humbling – particularly understanding the risks they face in such as highly prohibitionist policy environment.

I was in Kenya with Cara Lavan the lead film producer on our Anyone’s Child campaign (www.anyoneschild.org/video), and also a member of the UK’s Anyone’s Child group. Lugard had arranged a week of interviews for us to film with key figures leading the debate on the need for reform in the city. We will be turning these into short films to use as a resource in our advocacy work – watch this space.

Our week included visiting and interviewing a police officer, a bishop in his church, a judge at the law courts, drug users and human rights advocates. The interviewees explained more about the situation in Kenya, the realities on the ground and why they were supporting Lugard’s efforts to raise the debate in Kenya.

We also interviewed three family members involved with our Anyone’s Child project about their stories. This included Erik whose brother has for many years been a problematic heroin user. We interviewed him at his workplace – a community project he had just founded offering music and cooking facilities to under-employed youth in an effort to combat radicalisation in the area. He spoke of his ongoing struggles and frustrations with his brother around his drug use but observed how criminalisation and police brutality had added to his brother’s problems and further alienated him from society. A health based policy would surely be more effective, he argued.

We then met Meswaleh and her daughter, Fatuma, in their home in a very poor area of Mombasa. The two women were busy washing in a bucket and the rain was pouring when we arrived. The tin roof above us was leaking – apparently drug users and homeless people sleep there at night, ‘at least they are more safe there’ the mother and daughter explained, as we were setting up the filming equipment. The mother told us her story.

She spoke of her son and how as a child he’d suffered from polio and was left barely able to walk. As a teen, he’d started using heroin as a way to self medicate. A drug user yes, but the family were keen to emphasise how kind and caring he’d been, how he’d never steal – he worked hard, even holding down a job despite his disability – and how it was the criminal involvement around the trade that had killed him. The mother was now left with little income as she’d been financially reliant on her son.

Finally we met Zahra, the chair of the Anyone’s Child Kenya board, in her home in the suburbs of Mombasa – a beautiful, middle class area. Her son too had suffered problems from drugs, leading him to turn to criminal and abnormal behaviour. Zahra has lived in secrecy with her son’s problems for years but she now feels the time has come for her to speak out. Zahra is keen to encourage others to speak out as well and has been at the forefront of championing Anyone’s Child in Kenya.

What was so striking for me was the incredible similarities between the stories I heard in Kenya – even between very different classes – and how they covered the same hopes, dreams and fears of families all over the world, including here in the UK. Yes, some of the stories are more extreme than what occurs in the UK, but the stigma is so similar and the impacts of criminalisation of the drugs market is destructive in the same way. Families are forced to live in silence and fear that their community will judge them and those around them – it seems to me to be that this is the same the world over. This is why I feel it is so important that these stories are shared. Because ultimately as our campaign says, drugs can impact Anyone’s Child.

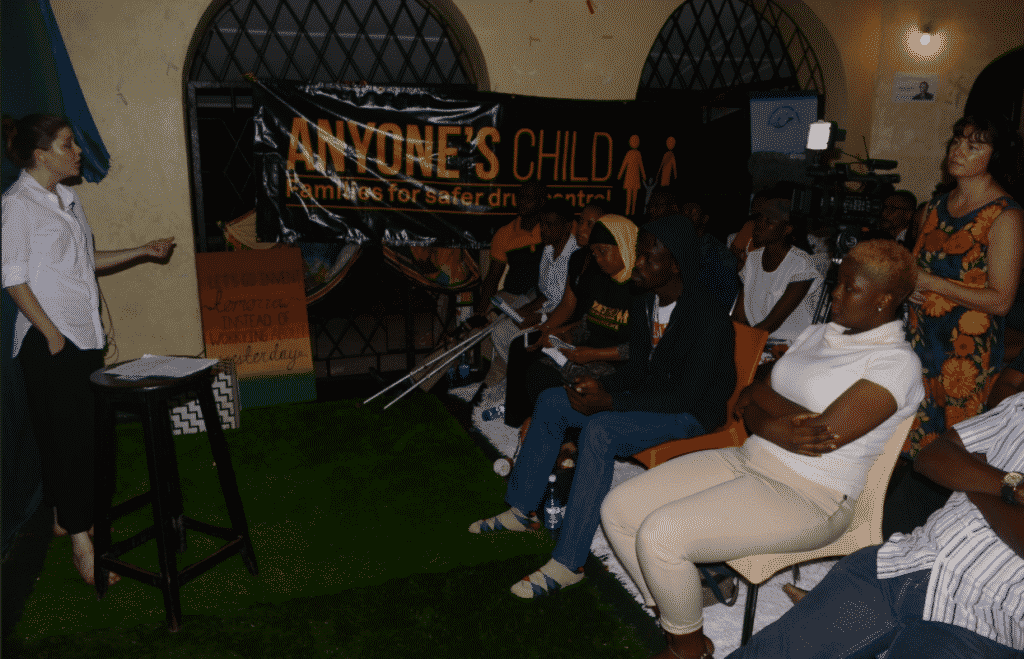

The week culminated in the launch event which was delivered in conjunction with Ufalme Africa an arts youth group based in Mombasa. It was uniquely Kenyan and truly beautiful – a night of speeches interwoven with songs, dances and poems about the Anyone’s Child campaign. (The group had studied the Anyone’s Child website and made their own interpretation to fit the local context – truly inspired). The evening was sold out, with over 100 people in attendance and guests filling the stairs and hallway. By the end of the evening, the whole room was singing and many of the families involved in the project were at the front – arm in arm singing for peace in the upcoming elections, for solidarity and for better drug laws.

Zahra gave us a lift back to our accommodation after the launch, and on the way we stopped briefly for some food with her family. Over dinner in Swahili, Zahra’s daughter-in-law spoke out to Zahra for the first time. “My brother was impacted too” she said. “He died several years ago and had been a drug user”. This was the first time they’d discussed the issue openly. It had taken the evening and the warmth and support of the room, with so many people speaking out, for her to have the courage to join in.

I have lots still to digest from my trip, but I hope and look forward to the Kenyan project flourishing. We now need to raise the volume of our voices, to continue to attract media to the cause and to have genuine conversations about these difficult issues at every opportunity. That Kenya is starting to have this discussion should be a wake up call to us here in the UK. These discussions need to be happening more here too.

Author: Jane Slater, Campaign Manager for Anyone’s Child

Sounds like it was an amazing and really worthwhile journey.