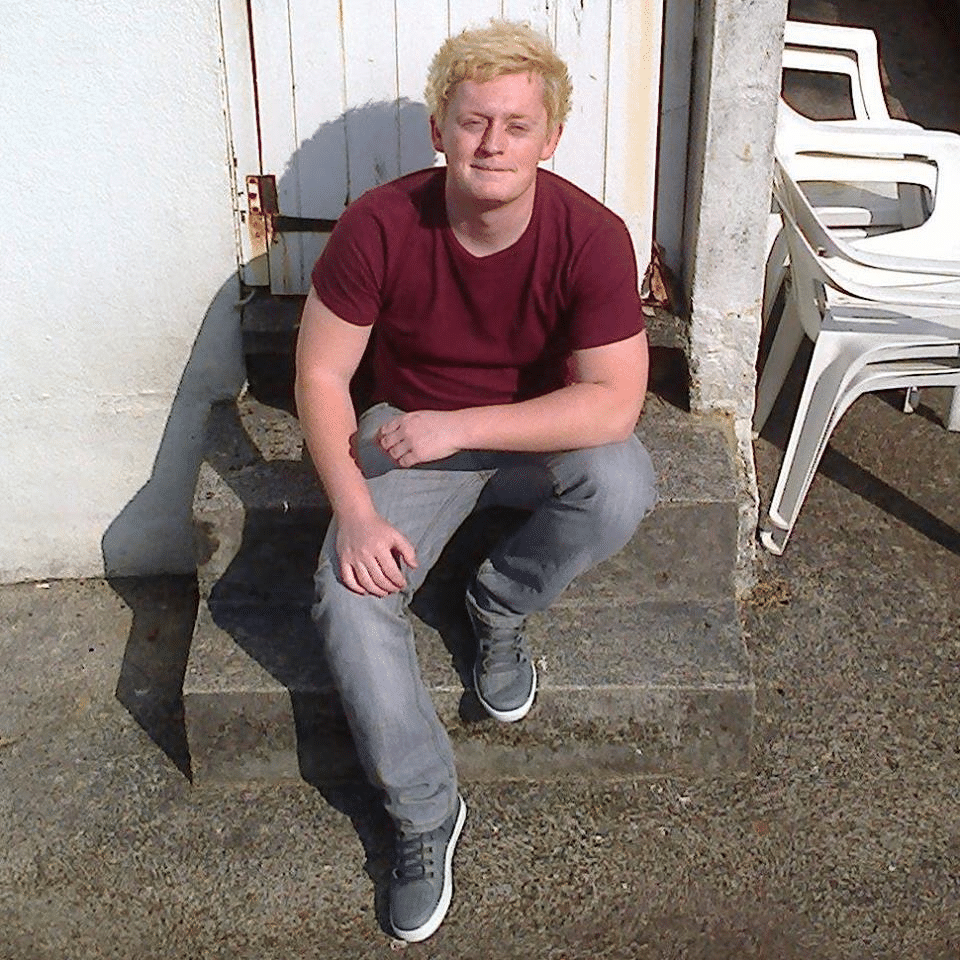

My son Jake was smart, funny, sensitive and the joy of my life. He was arrogant and reckless too, and started to use substances in his mid-teens. I will never be sure why he started but I am absolutely sure that his death in May 2016 at the age of 22 could have been avoided if his condition had been viewed as medical and not as a lifestyle choice. Jake was placed on a UK methadone programme in January 2014, which would work to a point until they insisted on starting a reduction without anything else having been put in place.

After two years of methadone treatment, coming off, using heroin and back to methadone, no progress had really been made and my son’s state of mind was now severely compromised. During this period one astute mental health nurse thought Jake may have an underlying syndrome and referred him for an Autistic spectrum assessment. This took place but, and I quote, “Despite demonstrating most Asperger’s behaviors, a diagnosis could not be given officially because of his misuse of substances.”

After a spell in hospital with pancreatitis in January 2016, the services made the decision to terminate his treatment completely, ordering a swift reduction down to nil methadone. This decision was taken because (and this was discussed at a risk assessment meeting) if my son Jake were to die, the services could not afford for their methadone to be in the mix. Jake was cut adrift from services and from medication. He went back to buying street heroin, which he smoked, having found the determination to stop injecting somehow.

He was rapidly running out of funds and though I saw him every day and provided food and showers when he asked, I had resolved never to provide cash. I now question this decision every day.

On May Bank Holiday 2016, Jake decided to use the last of his money to go on a holiday to Bangkok where he had been twice before. He knew that he could obtain over the counter opiates there at minimal cost and had a crazy scheme to detox himself from heroin and return home after four weeks with a less problematic and less expensive Tramadol dependency. It was madness; all the family felt it, but no one could stop it.

For 22 years I saw or spoke to my inimitable son every day, either in person or via e-mail, phone or Facebook. When I did not hear from him for 48 hours, I think I knew.

Jake died alone in a hotel room, in Bangkok, five days before his booked flight to return home. He was not found for 24 hours. He was not fit for viewing when I arrived in Bangkok . I had no choice but to cremate him there. I never saw him. I could not dress him nor place treasured toys in his coffin. I was denied the usual rituals of death. We have no grave or headstone, just his ashes in a box in my bedroom. I am still stunned and wounded anew each morning with the realisation that he is never coming home.

His death has altered me profoundly and my views on our drug laws have changed and developed.

He died because he was thrown upon his own resources when he was in need of medical support. He had convinced a Thai hospital to prescribe MST tabs (30 mgs) and had somehow miscalculated – his first and last error.

If my son had been offered a Heroin Assisted Treatment Plan where he could have obtained a daily dose of what had become for him a necessity to remain stable, then I believe he could have gone on to achieve his potential. He had attended a top grammar school a year early, was a high achiever and had a place at a Russell Group university. He had friends, a loving family and a potentially successful future. In all his years of addiction, he did not steal, was never arrested and did not acquire a criminal record (this was one of his fears and regulators). He only used bad language against me, his mum, once. He was always included in our family. I once sent out an e-mail to all my family and friends which said, “Jake is a heroin addict but I have decided to love him anyway.”

Jake was not bad, but ill. There were no suitable treatments available for someone who had developed mental health issues, unacknowledged high functioning Aspergers,and an opiate dependency.

Jake needed a change of law that would recognise his need and treat him accordingly. The current law does not work to save lives. My son Jake had to liaise with criminals to obtain what had become essential to him. He should have been able to go to medical professionals to get help. Had this been the case I believe he might still be alive today.

I miss him.

I love him.