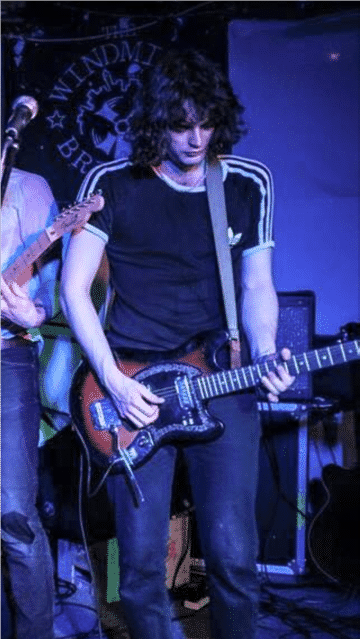

George was a highly intelligent, articulate and talented musician and poet, graduating with an honours degree in English in 2015. He had suffered from recurring bouts of severe depression since he was 14. His behaviour could be very challenging at times, especially when suffering from his demons.

In 2014, while at university, he started using heroin. Access to psychiatric services was difficult. He was persuaded to seek help and became a patient at New Directions (now CGL) in London, where he lived. He succeeded in coming off heroin by May 2015 and was well over the summer of 2015 when he got his degree.

However, he became depressed again, and started taking drugs again. He found it difficult to organise himself to get a referral to see a psychiatrist through his GP, so saw a psychiatrist privately in November 2015, but declined inpatient admission to manage his addiction. He wanted to be able to live in a normal environment.

He then relapsed into heroin use and returned to CGL in December 2015. He stabilised again on buprenorphine (an opiate substitute treatment).

George tried to access mental health services in February 2016 to deal with his depression. His application was rejected in March 2016. This was in spite of expressing suicidal ideas. The reason given was that he was on prescription opiates. No alternative therapy or appointments were offered.

He understood that had to be off all opiates for six months at least, before being granted access to mental health services. This was devastating for him at the time, but made him determined to come off buprenorphine (which would have protected him from taking street heroin), in order to be accepted by mental health services. He felt thoroughly rejected and, as his mother and a senior NHS clinician myself, I was aghast.

He weaned himself off buprenorphine entirely, and was consequently discharged from CGL in April 2016 with no follow-up in place. I feared that he would relapse, and because of this, was communicating with him every few days, as was his girlfriend and father, to try and support him through such a vulnerable period when his depression was uncontrolled.

As an interim measure, he accepted the support of a private psychoanalyst who was seeing him 2-3 times a week. This may or may not have been the right therapy. His GP had prescribed him antidepressants – but the medication was unable to control his depression. At his inquest, it emerged that the GP had no training in psychiatry (and was fairly junior). He desperately needed to be seen by an experienced psychiatrist and have his depression appropriately treated.

I spoke to him on the evening of Thursday 16th June 2016 and he was well, feeling positive and determined not to be seduced by street heroin. If he had been getting the right psychiatric support for his depression, had still been taking buprenorphine or been offered other options such as Heroin Assisted  Treatment (HAT), ideally under the care of the same service provider, I don’t believe he would have succumbed to using street heroin. He was found dead on 18th June due to a heroin overdose, by his girlfriend who I had asked to check up on him; he had not been responding to me trying to contact him.

Treatment (HAT), ideally under the care of the same service provider, I don’t believe he would have succumbed to using street heroin. He was found dead on 18th June due to a heroin overdose, by his girlfriend who I had asked to check up on him; he had not been responding to me trying to contact him.

George’s inquest was on 12th April 2017. The coroner requested an action plan to address the issues we raised in relation to the disconnection between mental health and addiction services. The services are commissioned differently (local authority for addiction and NHS for mental health), and so work in silos – something George always lamented. He resorted to taking heroin as it made him feel so much better but would have preferred his depression to be properly treated.

George was stigmatised as a result of his addiction by mental health services and the police. He was treated as a criminal when he was a very ill young man. The Mental health services were dismissive. The police had no interest in pursuing his killers – the drug barons who control the dealers selling drugs of unknown potency and purity.

He was failed by a flawed system. Addiction should be treated as an illness and drugs should be regulated. Had George been able to access Heroin Assisted Treatment and not been forced to access street heroin, the strong likelihood is that he would still be alive today.