Let’s stop judging and start listening.

By Hilary Mills

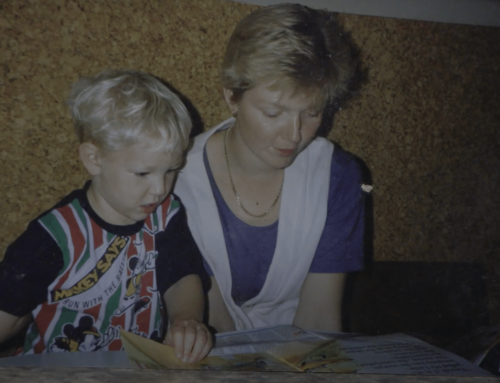

How can it be possible that seven years have passed since my son Ben died from a heroin overdose? Some days, it seems like it was yesterday; the pain in my heart feels so sharp, my stomach feels like it’s been hit by a bowling ball, and I can hardly breathe. Other days, it feels like a lifetime ago, and it’s more of a dull ache—a sadness that hangs around even in the middle of joy. I get into a panic that people will forget Ben. I close my eyes and worry I’ve forgotten what he looks like. It’s strange; however painful losing Ben has been, I want to hold on to some of that pain because letting go of it is like letting go of him, and I never want to let go of him. I never want to leave him behind. He is a part of me always.

When you lose someone to a drug dependency, you’ve not only got grief to deal with; you’ve also got the many other emotions that come with it—guilt, shame, isolation. You start questioning everything; your mind runs through every interaction you’ve ever had with them, and you replay every conversation, wondering if things could have been different, if there was anything you could have said or done that would have made a difference. Would they still be here if you’d done this or that? It can torment your mind if you let it.

Grief isn’t a straightforward journey; it’s full of twists and turns, unpredictable, and an ever-evolving emotion. I’ve tried to look for answers: was Ben’s death avoidable? Was there anything I could have done differently? But I’ve had to come to the realization and acceptance that I can’t change the fact he has died. However, I can help others struggling under the grip of dependent use and perhaps prevent the same thing from happening to another family. I can use his death to help others and still be his mum, just in a different way. By speaking out, having these discussions, and talking honestly about drugs, is a small but significant step in reducing the shame, misconceptions, and stigma around not only drugs but also addiction.

I joined Anyone’s Child about four years ago. Before that, I also had many uninformed views. I thought we should make it illegal, punish those who use drugs, and believed they could control it—just tell them it’s bad, and assume they come from a bad family—these were all assumptions. But after listening, researching, and digging a bit deeper, I began to realize how significant a problem problematic drug use is. It affects so many in society—from families and communities to education, health services, police, businesses, and most of all, our young people. It’s almost at pandemic levels, with death figures rising each year, prisons overflowing, and our health services struggling. We are losing this so-called war on drugs, so clearly something is wrong. Maybe these attitudes and approaches to dealing with the problem aren’t working, and perhaps we need to do something different.

I’ve realized because there will always be a demand for drugs, and they are illegal, the criminals who sell and produce the drugs have a complete and utter monopoly on the market. They have no regulations or concern for their “customers.” In fact, the more people who become addicted, the better their profits. Because drugs are illegal, the risks are greater, so the profit is higher. To keep control of their “business,” they use violence and threats. People become stuck in a cycle they cannot escape, and so it goes on.

As long as there is a demand, there will be a business. When this business is in criminal hands, it makes drugs even more unsafe and causes even more harm. If you could produce the same drugs, with the same effect, but regulated and legal—like cigarettes and alcohol—you would put many criminals out of business. You could tax it, have fairer prices, provide better informed and honest education, and reduce the strain on our police, crime, and health services.

In the 4 years I have been campaigning with Anyone’s Child, I have organized a couple of events, bringing key stakeholders together in my local area—representatives from the police, health services, mental health, drug services, homeless organizations, and family support—and having these really vital conversations about how they can best support those with a drug dependency and family members affected. I found there is often a lack of communication between services, and it’s good that they can link up and share experiences and ideas on how best to support their clients. Drug dependency often has roots—reasons why individuals may have become dependent or started to use drugs. It’s no good tackling the problem halfway, putting people in the criminal justice system, making things illegal, and thinking this will stop harmful drug use. It won’t. If you start looking at why people take drugs—i.e., social situations, poverty, trauma—and tackle these issues, you are more likely to reduce harm. As human beings, we don’t like to feel pain, and for some, taking drugs is a way to find relief. They are actually doing what any human would do—try to eliminate pain. Is it then right to stick them in prison, isolate them, and pin a criminal label on them?

I have seen improvements since joining Anyone’s Child, drug overdose prevention centres in Scotland, more and more drug diversion in policing, better training, and improved communication between mental health and addiction services. Things have moved forward since Ben died, but until there are actual changes in legislation, drugs and all the criminality surrounding them will continue to cause harm, deaths, and broken families. As I slip into another year without Ben here physically, I hope that things continue to move forward. It doesn’t matter if it’s just a conversation or listening to each other; these simple actions make a huge difference. Many people living with addiction are isolated, so just showing you care, resisting judgment, and allowing them to talk will help save lives. When you start caring for them, they start caring for themselves. As Ben once said to me, “I just want to be like everyone else.” He had so little self-belief or confidence; he didn’t feel good enough. Let’s stop judging and start listening.

Leave A Comment