We were delighted to speak to the award-winning photographer, Carlos Villalon, about his new book “COCA: the lost war”. Carlos has spent 16 years documenting the journey of coca in the Americas, from the sacred coca plant to cocaine, through the stories of individuals he met along the way. Embedding himself in the world of guerrilla and paramilitary groups, drug cartels and coca growers, people who use drugs and their families, Carlos has witnessed firsthand how fighting the drug war has caused appalling death and destruction. Beyond illustrating the devastating impact of drug prohibition, Carlos hopes that this book will be a powerful tool to help bring about safer drug control.

We were delighted to speak to the award-winning photographer, Carlos Villalon, about his new book “COCA: the lost war”. Carlos has spent 16 years documenting the journey of coca in the Americas, from the sacred coca plant to cocaine, through the stories of individuals he met along the way. Embedding himself in the world of guerrilla and paramilitary groups, drug cartels and coca growers, people who use drugs and their families, Carlos has witnessed firsthand how fighting the drug war has caused appalling death and destruction. Beyond illustrating the devastating impact of drug prohibition, Carlos hopes that this book will be a powerful tool to help bring about safer drug control.

- Please can you tell me a bit about your new book?

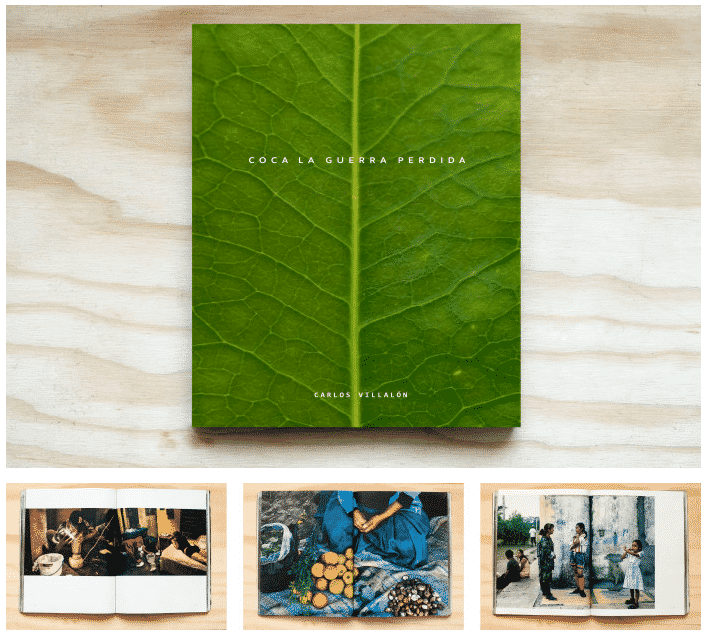

“COCA: the lost war” is a photo book – it has 73 colour photographs in it. It also includes four personal contributions from individuals I have great respect for due to their work on drugs. First we have Wade Davis, an ethnobotanist and explorer from Harvard University who is probably the world’s leading expert on the coca plant and its significance for the indigenous cultures for whom it is sacred. Ethan Nadelmann, the founder of the Drug Policy Alliance in the United States writes an incredible essay about how the war on a drugs has failed. Then my good friend, British journalist Karl Penhaul – formerly with CNN International – writes about our journey in Colombia and Mexico. And finally, Calixto Kuiru, a shaman from the Amazon rainforest has contributed a short essay explaining why coca plants are so important for his people, his clan. So you have 73 colour photographs with these four texts, a map and a timeline about coca and cocaine.

- What story are you hoping to tell through your photographs?

The book has two angles – and both are very important. The first is to show that coca plants are sacred to some cultures in the Andes and the Amazon rainforest. I think, as Wade Davies puts very well at the end of his essay, if you eliminate coca plants, you are going to lose the culture and with it the history of these indigenous groups. It would be a catastrophe.

Secondly, we have the ‘War on Drugs’, created by Richard Nixon – which has been going on for so many years and has showed no results. The only thing it has caused is suffering and bloodshed, lots of people killed and disappeared and lots of poverty. We have more drugs in the street, we have crime, we have thousands of minorities in jail and nothing has changed. I ask, why is it that politicians are so interested in continuing to fight this war when it’s not working? Really we should be looking to alternatives to stop this war and to change drug policy. That’s the other thing that I want people to look at in these photographs and in this book.

- What do you think your photos say about drug policy?

I’m always looking to photograph the real people impacted in this war, so that you can see them as they are, ordinary people. These people are human beings. Some of them become caught in the middle of the drug war because they have no other alternative. They are victims, people who are paying a price because of the place they live in, the situation they live in, the political situation they are in, or even the country. I’ve come to see that people who use cocaine shouldn’t be blamed for causing this mess. If you do a line of cocaine, you’re doing nothing wrong to anyone – maybe you’re doing something wrong to your own body but that’s your own business. We shouldn’t see these people as guilty, the only guilty people here are the politicians who are in charge of drug policy.

My main idea behind the book has been to give people the tools to talk about and debate drug policy from a well-informed point of view. I hope that when people look at my work they will feel compelled to talk about it. This is the only way that we can change this world, by talking among ourselves and trying to convince our politicians that this is very wrong and needs to be changed. I want people to be well informed because then we can create alternative solutions to these problems we have.

- How do you think we could make drug policy better fit the needs of the people shown in your photographs?

Well I think we need to change our drug policy. It’s obvious that when you legalise something that is illegal, it loses its criminal market value. If you legalise these drugs you can keep control of them, you know who’s buying them and you would be able to end this war. Rather than cartel fighting against cartel, government fighting against cartel, drug gangs fighting against other drug gangs, we could help to stop the violence through legal control. You regain control of what you legalise and I don’t see many problems with this.

- Could you tell me the story of the people in these photographs?

These kids are carrying coca plant cuts on a plantation that was fumigated just a couple of days before. They get the cuts from the bottom of the plant and they take them to a new plantation and grow them again. It’s actually really difficult to kill the coca plant with pesticides.

They are farmers, they don’t even call themselves coca farmers, just farmers. To them, coca is just another crop and everyone works with it. They don’t see it as an ‘evil’ plant, like many of us do, for them it’s just a crop. They always tell me that they would prefer to work with a legal crop and have the backing of the government but currently this isn’t an option because of the lack of infrastructure, the war and the government.

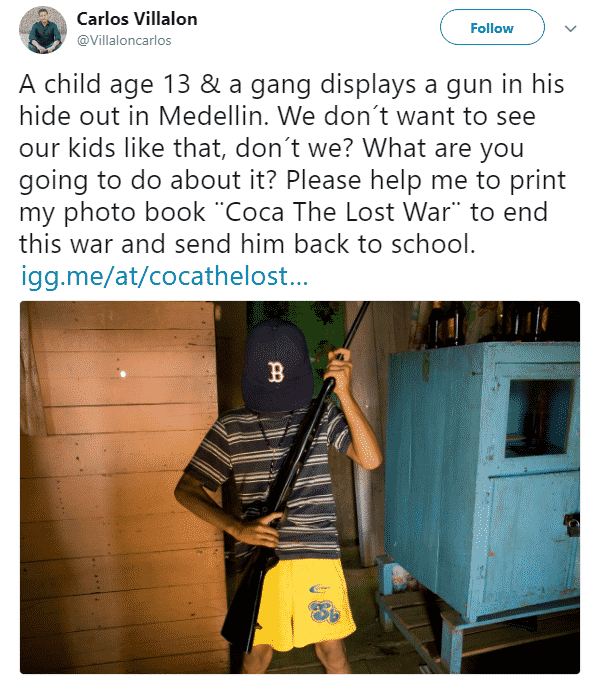

This is the family of a child called Luis Felipe López. He was 16 years old when he was sitting on the sidewalk with his girlfriend and a car stopped, shot him and killed him. What you can’t see in the picture is the boy’s body. And this is his family, hugging.

The photo was shot in Acapulco, Mexico. I was there for a few days, hanging with some local photographers so that they could show me what it was like to be on the frontline of the war on drugs. When they go to these crime scenes they agree to photograph only the dead person. So every morning you look at the newspapers and you see these dead bodies on the street. And I didn’t ask them why they had agreed to do that – maybe it was the cartels threatening them, I don’t know.

But I decided to talk to the families. The mother of this boy looks at me and she says “Please. Please take my picture, I want to tell you about what’s going on. I want to tell you about why they killed my son. And I don’t understand why no one ever talks to us. The only thing we see is dead people in the papers next morning and no one ever talks to us.” That showed me that people really want to talk about how they are suffering, about this war that they are immersed in and have nothing to do with. They want the world to know what is going on. We cannot know if this kid was involved in drugs, but his mother swore that he was a good kid, going to school, and I believe her. She’s the one in pain there and she’s saying what’s going on. But it’s nothing strange to have these drive-by shootings in these type of cities. This is why we need to stop this war. You have all these people suffering and living in poverty and then you bring war to these places. We need to stop this, it is ridiculous. And to stop it, we must legalise and regulate the drug market. You can support drug policy reform and buy ‘COCA: THE LOST WAR’ here: https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/coca-the-lost-war-coca-la-guerra-perdida-books#/ Read Luz‘s story, our latest Anyone’s Child member, to hear how fighting the drug war has torn apart the lives of families and communities in Colombia.

Leave A Comment